Relevancy and Engagement

dc.agclassroom.org

Relevancy and Engagement

dc.agclassroom.org

Federal Lands: Ranching & Recreating on Common Grounds

Grade Level

Purpose

Using various forms of maps, students will analyze public lands in the western United States, describe how ranchers raise food and fiber on federally owned land, and discuss different points of view concerning public lands use and public lands grazing. This lesson covers a socioscientific issue and aims to provide students with tools to evaluate science within the context of social and economic points of view. Grades 9-12

Estimated Time

Materials Needed

Engage:

Activity 1: The Wooly, Wooly West

Activity 2:

- Digital device and internet access, 1 per group

- America's Public Lands: History, Origin, Future PDF (digital access)

- Public Lands Timeline handout, 1 per group

- Poster paper or large sheets of paper, 1 per group

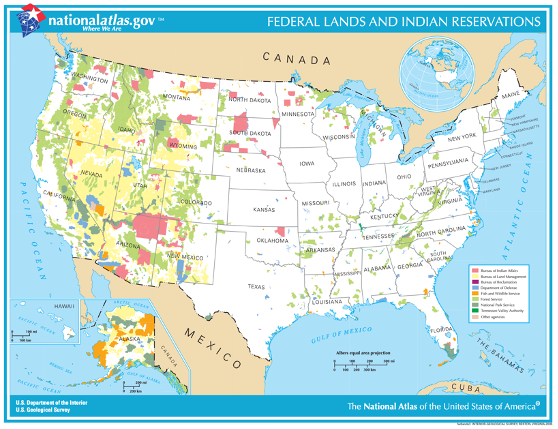

- Federal Lands and Indian Reservations Map

Activity 3:

- Federal Lands Points of View Cards, 1 set per class

- Beach ball or soccer ball

Vocabulary

graze: to feed on grass

natural resources: materials or substances such as minerals, forests, water, and fertile land that occur in nature and can be used for economic gain

Did You Know?

- The federal government owns roughly 640 million acres, which is about 28% of the 2.27 billion acres of land in the United States.1

- Livestock grazing represents the earliest use of public lands, leading our nation's westward expansion.2

- About 40% of beef cows in the West and 50% of the nation's sheep herd spends time on public land.2

- Ranchers are responsible for conserving and maintaining seven million acres of sage grouse habitat.7

Background Agricultural Connections

The federal government owns roughly 640 million acres—about 28%—of the 2.27 billion acres of land in the United States.1 There are four major federal land agencies who manage and maintain 600 million acres of federal land including the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), National Park Service (NPS) in the Department of Interior, and the Forest SErvice (FS) in the Department of Agriculture. These four agencies manage federal lands for many purposes related to preservation, recreation, and the development of natural resources. The remaining 40 million acres of federal land are managed by the Department of Defense and other federal agencies. In the United States, the percentage of federally owned land in each state varies; however, federal land ownership is predominately found in Oregon, Washington, California, Idaho, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico.

Where did Public Lands Come From?

Federal land in the United States was acquired through various cessions and purchases. This includes land ceded from Native Americans, lands relinquished by the colonies, the Louisiana Purchase from France, the Mexican Cession, the Gadsden Purchase from Mexico, and the Alaskan Purchase from Russia. The original public domain lands totaled 1.8 billion acres.4 Two-thirds of the original 1.8 billion acres of public domain were eventually transferred to individuals, corporations, and states. Other large areas of land were set aside for national parks and monuments, national forests, wildlife preserves and refuges, military lands, and federal reservations for Native American Tribes.4

During the 1800s, Congress passed laws authorizing the disposal of public lands to citizens, states, and private companies to encourage settlement and development of the West. Most of the federal lands were transferred out of the public domain by military bounties, land grants to states, railroads, and wagon roads, and land transfers to individuals. An estimated 640 million acres—including both surface and mineral rights—were transferred to those who settled the Midwest and West. Read more about the origin and history of public lands.

Raising Food and Fiber on Public Lands Today

Ranchers who grazed livestock were the primary users of public lands until 1960 when the public started becoming more interested in public lands. The Multiple-use Yield Sustained Act of 1960 and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 required multiple-use on public land. This means that everyone has a place on public lands whether they are hiking, camping, fishing, hunting, or ranching. Today, 22,000 ranchers hold grazing permits on more than 250 million acres managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service.7 These ranchers own their own land, but also pay an annual fee to the government for grazing permits which allows livestock to graze on public lands. Nearly 40% of western cattle and 50% of the nation's sheep spend time on public lands.7 Ranchers not only graze livestock on the range, but act as stewards of the land as well. If done correctly, livestock grazing can be an essential land management tool through efforts including preserving clean water sources, controlling invasive plants and non-native grasses, protecting the habitat for endangered species, and maintaining firebreaks to actively prevent forest and range fires.7

Public lands continue to see a significant increase of environmental, agricultural, and recreational use which can lead to disagreements and conflict between federal agencies, ranchers, and the public. Land owned by the federal government for multiple uses is essential to the health and well-being of rural communities, livestock producers, and those who come to enjoy recreational activities. Each use carries specific benefits and consequences that affect people and the environment, and no one group—or use—should take precedence over others.

Engage

- Project the Common Grounds Photo on the board and ask students, "What do these photos all have in common?"

- Allow students to share throughts and brainstorm ideas. Make a list of the students' ideas on the board.

- Do not give students the answer at this point. Instead, return to the Common Grounds Photo at the end of the lesson and discuss what each photo has in common.

Teach for ClarityIt is important to note that federal land acquisition from Native Americans and Indigenous peoples is an important topic that relates to today’s use of public and federal lands. This lesson primarily focuses on today’s current rules and regulations of public and federal lands—specifically agricultural use and livestock grazing—and not the acquisition of federal lands. As appropriate, you may further discuss this topic with students and acknowledge lands or territories of Native American tribes throughout the United States. Click here for more information. |

Explore and Explain

Activity 1: The Wooly, Wooly West

- Begin by projecting the Interactive Sheep and Wool Maps on the board.

- Ask students to study the maps and consider the following:

- What do the various colors on the maps represent?

- Which region(s) in the United States raise the most sheep?

- Which region(s) in the United States produce the most wool?

- What are the top 10 sheep-producing states?

- What are the top 10 wool-producing states?

- How can the top sheep-producing states differ from the top wool-producing states?

- Some sheep producers raise sheep specifically for breeding and meat production. Other sheep producers raise sheep for meat production who also have high-quality wool that can be sold.

- Project the Federal Lands Map on the board.

- Ask students, "Is there a correlation between the sheep/wool maps and the federal lands map?"

- Project the maps and table below on the board.

- Ask students to analyze the relationship between the maps. Ask students, "If the western states are predominately federally owned, AND the top sheep- and wool-producing states are also in the western states, where do ranchers raise all of these sheep?"

- Using information from the Background Agricultural Connections paragraph, explain to students that many ranchers in the West utilize federal land to graze sheep and cattle. The ranchers obtain permits or leases from federal agencies to raise livestock. Ask students to consider the pros and cons of using federal land to graze animals throughout the remainder of the lesson.

Activity 2: Public Lands Timeline

- Project the Federal Lands and Indian Reservations Map on the board.

- Divide the class into six different groups so there are 3-4 students in a group. If a class is too large, assign the same category to multiple groups.

- Assign each group a topic from the History of Public Lands PDF.

- Group 1: Where did the public lands come from?

- Group 2: What happened to the original public lands?

- Group 3: Federal Land Agencies

- Group 4: Emergence of the BLM

- Group 5: New laws, New Uses, New Identity for the BLM

- Pass out one Public Lands Timeline handout to each group.

- Allow students to work in groups to read the History of Public Lands PDF. Students should address the questions and topics from the Public Lands Timeline handout and include them on their group timeline poster.

- Note: to supplement students' reading and knowledge, digital access to Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data can be given to students as well. This document includes maps, data, and further details on federal land ownership.

- When groups have finished their posters, ask one member from each group to bring their poster to the front of the class. Ask students holding the posters, ask one member from each group to bring their poster to the front of the class. Ask students holding the posters to stand in order, creating a sequential timeline of public lands.

- One at a time, have each group spokesperson present their material. Students should build upon the previous groups' posters and information as they go.

- Interject, if needed, to discuss key topics such as land grants, acts, laws, and federal agencies.

- Again, ask students to consider the same question as earlier, "What are the pros and cons to grazing livestock on federal land?" Also ask, "How do federal lands and public domain benefit Americans?"

Activity 3: Federal Land Use from Different Points of View

- Write the numbers 1-6 on a beach ball or soccer ball.

- Now, stand in the middle of the room and hold the ball up for students to see. Without rotating the ball, ask students in various points of the room which number(s) they can see. For example, ask a student in the front of the classroom what number he or she sees, followed by the same question to a student in the back of the room and so on. Each student will see all or part of different numbers.

- Ask your students, "Why, if you are all looking at the same object (the ball), are you seeing different numbers?" Explain that it is because each has a different "point of view." Each student sees different numbers from their point of view. They may see an entire number or part of a number. There will be some numbers that they do not see at all.

- Use this object lesson to spring into a discussion about federal land use in the western United States.

- Ask students, "What different points of view should be considered when discussing agriculture and federal land use? How could this be a controversial topic?"

- Allow students to share and discuss different points of view related to grazing livestock on federal land.

- While holding the ball in the middle of the room, divide students into six groups based on where they are sitting. Ask each group which number they see best from their position in the classroom. The number that they see will be their assigned point of view. For example, if a group sees the number one best from their position in the classroom, they will have card #1 and their point of view will be a beef rancher.

Note: Students may stay in the same groups as Activity 2 or be divided into new groups based on their view of the ball. - Using the Federal Land Point of View cards, assign each group a point of view to consider.

- Instruct groups to study the information on their card and discuss their point of view as a group. What other facts and information could be added to support their point of view? Groups should research their point of view and find various artifacts (e.g. video clips, news articles, opinion articles, etc.) that would help defend their point of view in a presentation or class discussion.

Note: If time is short, the information on the card should give them the baseline information that they need. - Allow students to present their material (point of view) to the class or set up desks for a classroom discussion on each of the different points of view.

- As each group presents or discusses their point of view, remind students of the following:

- It's okay to agree to disagree.

- When looking at or discussing issues, people may use facts, opinions, or personal biases to defend and persuade others to see her or his point of view.

- Resolving issues and evaluating situations requires that we look at the viewpoints of others to arrive at workable solutions, to form realistic conclusions, or to make our own evidence-based decisions.

Evaluate

- Project the Common Grounds Collage on the board from the Interest Approach—Engagement.

- Again, ask students what each photo has in common. Students should determine that each photo is something that can take place on public lands.

- Consider asking the following questions to lead a class discussion and promote critical thinking:

- How does public lands use benefit Americans?

- What are the consequences of public lands use?

- How can people who share different views and opinions effectively access and use public lands?

- What role doe sthe government play in the processing and distribution of food and fiber?

- Review and summarize the following key concepts:

- Federal lands in the United States—about 1.8 billion acres—were acquired through the Louisiana Purchase from France, the Mexican Cession, the Gadsden Purchase from Mexico, and the Alaska Purchase from Russia.

- Most farmers and ranchers work closely with federal agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and National Forest Service to responsibly graze livestock on public lands.

- Today, public lands are used by various groups including farmers, ranchers, hunters, miners, and recreational users. Each use carries specific benefits and consequences that affect people and the environment.

Sources

- https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42346.pdf

- https://www.ncba.org/CMDocs/BeefUSA/Issues/Public%20Lands%20Ranching%20Overview.pdf

- http://nefbmap.org/map.php?M=43&MV=0&P=35&PV=0

- https://publicland.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/150359_Public_Lands_Document_web.pdf

- https://www.trcp.org/2019/06/05/public-land-grazing-important-american-west/

- https://blm-egis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=6f0da4c7931440a8a80bfe20eddd7550

- http://publiclandscouncil.org/fact-sheets/

- https://www.fs.fed.us/rangeland-management/grazing/allowgrazing.shtml

- https://www.blm.gov/programs/natural-resources/rangelands-and-grazing/livestock-grazing/about

- https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RS21232.pdf